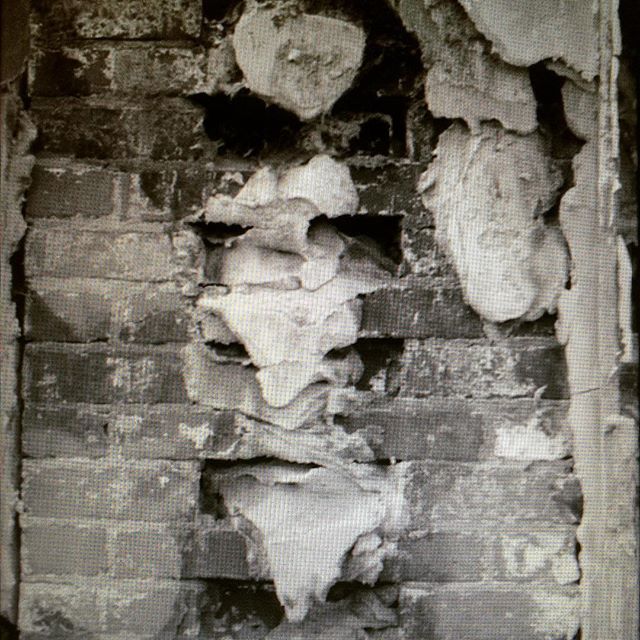

It’s been several years since I wrote with any regularity. Until recently I put this loss down to a break in my daily rhythms, in which I had let go of the space and time to focus on organizing my thoughts. I can’t say why, exactly, I allowed that to happen, but I suspect it grew out of a sense of the futility of writing.

I read a great deal; all day long, really. Books, articles, reports, proposals, blog and social media posts, correspondence and other ephemera. Most of these texts are in some way social. They are part of an interplay of conversation, their value is fleeting, and too often, they seem motivated, at least partly, by self-promotion. I noticed this with writing on Medium years ago. The algorithm that determines the content of my daily newsletter decided I was only interested in technology, self-help, and efficiency. It was, in short, about the platform itself: why I should write, how I should write, how to be more effective at writing, how to promote my writing, how to organize my work so that I could do more of it. Any platform that is mostly about itself deserves a swift death, no matter how lovely the font or balanced the kerning.

The Medium voice, slightly cloying, flattened of individuality, imbued with the aura of marketing, somehow demanding of attention and therefore disruptive, began to creep into other forums. First Twitter, which once felt unruly, playful and somehow vast and intimate at the same time, became dominated by self-promotion, snark and conformity. These voices began to overflow into editorial writing, as digital-first publications, fueled by VC funding, sought to achieve the exponential growth of technology platforms, and traditional media outlets followed, desperate for traffic and advertising revenue. Clamoring, insistent voices now dominate our public conversations, in all formats, and in many countries and languages. For every topic instant experts opine, and even when they are correct, and of course, they often are, it is simply exhausting. The most meaningful contribution I have been able manage, it seems, is silence.

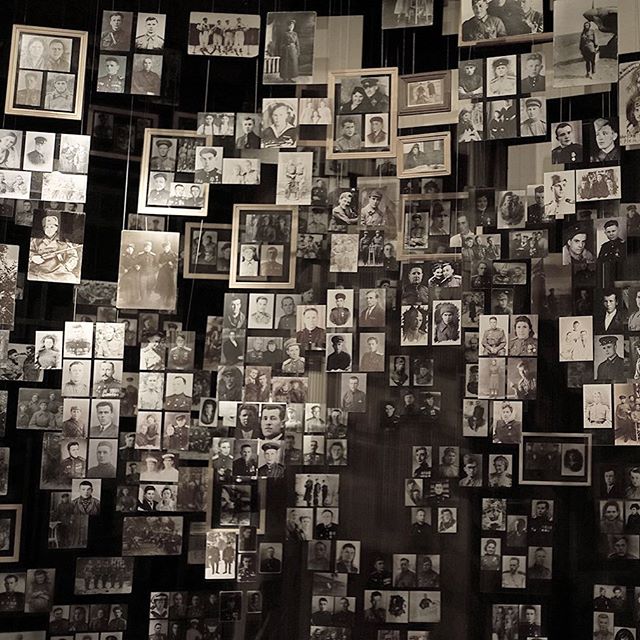

A few days ago marked a year since my last trip of any distance, to Italy and Nepal. For 30 years I have lived a peripatetic life, traveling monthly, and often weekly. When home, I walk, run, cycle, or otherwise find a way to be in motion. Motion is my medium; my calm, my respite, my joy. Travel is also a way of marking time and structuring memory: tickets, hotel bills, meals, encounters, physical efforts, wanderings, visits to museums and galleries, parks, bookstores, the abruptness of a season shifted by shifting to another location on the planet. Motion has been the measure of time, stasis (not stillness, which is often found with motion), demands another way to mark change. Perhaps a return to frequent writing can offer that, if I can find a way to practice it in a mode not in synch to attention engines, perhaps not online at all, and only if it is not about itself.