What shall we make of the flood of images and voices coursing through the Internet, and how shall we understand it? In our minds, the details of so much material overlap and overwhelm. On the Internet, we say, our attention is getting shorter, but our memory is improving. And yet, when I turn off my wifi, take off my glasses, and confront the flicker and hum of images in my own degraded memory, I know that the Internet’s recall will be as partial as my own. But, it seems to me, it will fail differently.

Human memories have half-lives. I remember seeing a video some years ago of two Russian football mobs clashing on a bridge. Red shirts versus blue, vicious kicks and punches, someone pushed into the water, the back-and-forth rush and blur of faces and bodies, all recorded by a shaky hand on a balcony overlooking the scene. I used to live in Russia, and I’ve been on those balconies; it could have been me standing on that slab of rotten concrete in the sky, camera in one hand, bottle of Baltika strong beer in the other.

When the Internet loses images they will be gone forever, replaced by a static screen and an epitaph: this video does not exist. Our organic recall might conjure a keyword: mob, hooligan, crowd, Spartak, Kiev, or we might try a knife fight + Russia + football Boolean search. It might survive in some screen grab, or appropriated under new metadata, but linkrot is an equally likely fate. Save for rigorous annotation and the hope that the company that built the tool in which you collected your citations might survive the latest corporate buyout, you are lost.

There are images of crowds, and there is the crowd of online images. They are not the same thing, but in our heads, and in the temporal flow of an Internet search, they merge into something resembling the fragility and confusion we feel when finding ourselves in a large and unpredictable mob. In the 19th century, an emerging social science literature considered crowds and decreed them monstrous, unruly, home to disorder of the human psyche and an existential threat to the nation-state.

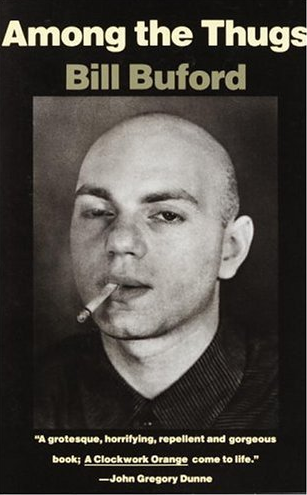

Twentieth-century thinkers absorbed that lesson and the idea of crowds retained a dark equivalence with mass violence. The writer Bill Buford immersed himself in the subculture of European football hooligans in the 1980s and dissected the creation and sustenance of crowds, finding that they were complex but knowable, with definite patterns, clear thresholds of behavior and markers that indicated a shift toward violence. His book, Among the Thugs, helped break the assumption that crowds were formed by something inherently unknowable and uncontrollable and placed them squarely in the frame of rational human behavior.

The Internet, in relocating the crowd onto networks, has shown us that crowd behaviors are in fact made up of many individual decisions, with resulting patterns that might be complex but can be measured. If a street crowd provides feedback for itself through sound, motion and threshold actions – a brick thrown through a window, a police line rushed – then a networked crowd has feedback loops that are transparent to anyone who monitors the network and knows that those loops provide direct and continuous input into our behavior. This has made it possible for us to imagine crowds in a wholly different light. Not just the wisdom of the crowd, but smart mobs, crisis mappers and even, in the parlance of labor-on-demand, crowd flowers.

Smart crowds do not, of course, necessarily mean good crowds. The testing ground for crowd behavior that is Tahrir Square has shown us everything from the peaceful vigil to rape as a tactic of terror. They do not cancel each other out, but coexist within our emerging understanding of complex crowd behaviors. Tahrir has also become the epitome of a crowd that simultaneously acts and documents itself as part of its action, creating its own self-monitoring feedback loops on Twitter, Flickr, Facebook and Bambuser.

It is in the Syria case that we find ourselves back on the unsteady analytic ground of the crowd as extra-rational threat. This time, it is the crowd of images of violence and protest that exist online, over 500,000 videos uploaded to YouTube alone. Out of the mass media comes a steady beat of fear associated with a lack of context and explanation of these images, as if their very lack of framing constitutes a danger. Here we also find a hazardous mourning for the loss of the iconic image made by heroic, trusted documentarians. These videos, even when existing within a definite network frame – YouTube user terms of service, required Internet access, user names, and a legal and technological underpinning – have somehow taken on an aspect of the unknown, or are being sold to us as such.

The consequence of this is subtle but significant: it degrades the authority and impact of those who make and upload them, and asks that we reassign legitimacy to the very media outlets and governments deriding them. These videos inspire derision, it seems me, primarily because they are complex and fragmentary narratives. They confound because they demonstrate the possibility of many competing positions of power, and block a satisfying resolution for those who seek a clear narrative, both in the media, and in governance. To deny their authority is to shift our focus away from the individuals involved, and their motives for creating and sharing their experiences.

This is perfectly exemplified by this video of Syrian citizen videographer Zaid Abu Obaida. The video shows Obaida filming a helicopter overhead, and explaining his motives for documenting: “we are trying to shoot it down through media by sending images to television channels with our simple equipment…we have nothing but these weapons.” Obaida himself was killed a few days later. This video is another epitaph.

This post was originally published on Global Voices.