This fall, Philadelphia’s Slought Foundation — an organization dedicated to engaging publics in dialogue about cultural and political change — hosted The Potemkin Project, an exhibition exploring the “falsification of reality in media and new frameworks for civic integrity.” In conjunction with the show, Slought brought Sam Gregory and me together for a gallery talk, “Weapons of Perception,” on November 1, 2019.

Slought had invited me to organize and curate the show, and also show images and films from my stint as Kluge Fellow in Digital Studies at the Library of Congress. This series, titled “Into The Fold Of The True,” features mixed media montage, collage, video, and code-based installation, composed from rephotographed and manipulated war propaganda taken from film and photography collections at the Library of Congress and other museum collections of war and conflict.

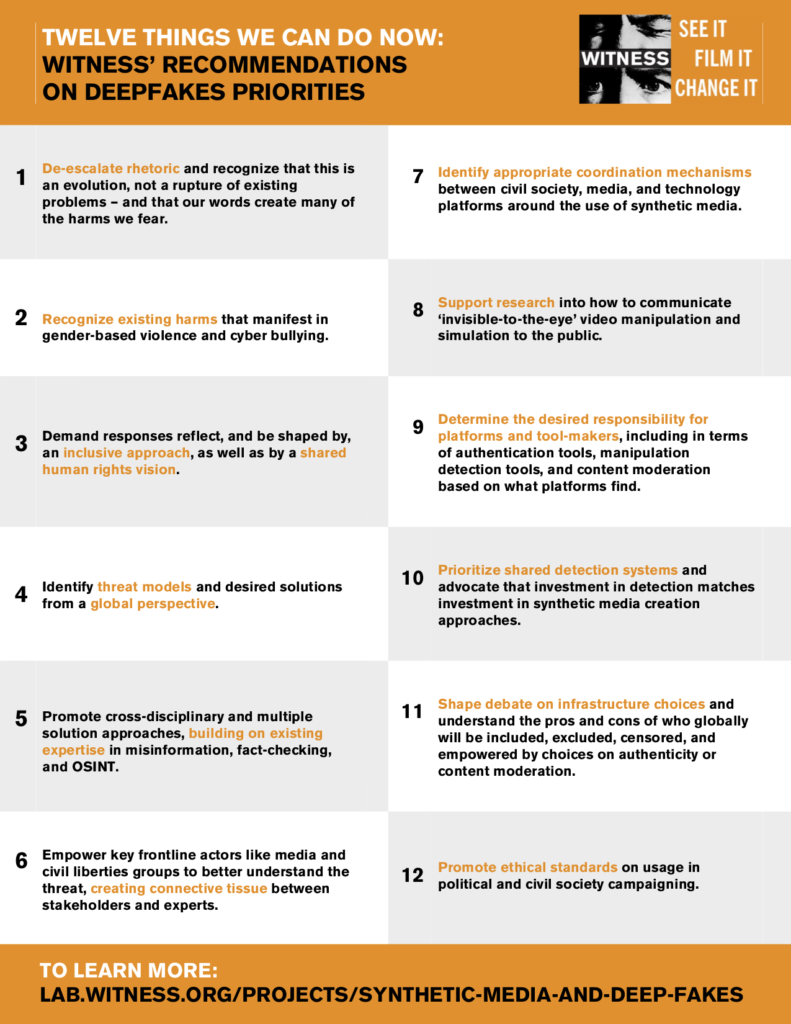

Gregory, the Program Director of WITNESS, exhibited materials from his human rights organization’s research into synthetic media and deepfakes. An expert on new forms of misinformation and disinformation as well as innovations in preserving trust, authenticity, and evidence, Gregory leads WITNESS’ global activities — in coordination with technical researchers, policy-makers, companies, media organizations, journalists and civic activists — aimed at building better preparedness for deepfakes.

This post was originally posted on Immerse, a platform for creative discussion of emerging nonfiction storytelling, hosted by the MIT Open Documentary Lab and the Fledging Fund.

Below, we present our conversation, edited for clarity and length.

SIGAL: I’ve been interested for many years in the question of how we represent violence. In 1996, I was a documentary photographer based in Russia, and I ended up photographing the Chechen war in Grozny. Over the next 20 years, as I covered and studied violent conflict and worked in news media, I noticed that editors often seek to use images familiar to their viewers. They seek images that respond to specific tropes that they had already predefined as part of their editorial policy. If you made images or suggested stories or narratives that didn’t fit within those preconceived ideas, they tended not to make it into the media.

That might seem like it’s just an artifact of a particular working culture, but the more I looked at it, the more I realized that this is something with a much longer history. Starting seven or eight years ago, I got more serious about this question, and I started looking at historical images of conflict.

Editors often seek to use images familiar to their viewers. If you made images or suggested stories or narratives that didn’t fit within those preconceived ideas, they tended not to make it into the media.

The first war photographed was the Crimean war, in 1845, by Roger Fenton. At the time, photographers relied on using a tripod; it generally took several minutes to make an exposure. Almost all of those images are static: men sitting on horses, landscapes, and other images familiar to us from that time period. Starting in the 1920s and the Spanish Civil War, with the advent of smaller cameras, we see a different trend line around the representation of violence. We see images of humans in motion: soldiers fighting, holding guns, seeming to have agency in their roles. Around the same time, basically from World War I onward, we saw the end of human agency in military conflict as war became massively industrialized, and individuals became fodder for cannons.

We’ve had a divergence between the representation of war with soldiers as heroes, telling stories from their perspectives, and a narrative frame in which soldiers’ actions are important to the outcome of war. The counterpoint is that modern war is constructed by economics, by supply lines, by advanced technology, by holding and keeping space. The individual as a fighter is interchangeable in a way that is both familiar to us and very tragic. Yet the way we represent conflict has not changed much in the last 100 years.

There are a small number of tropes for how we photograph and represent soldiers and others fighting war. It’s quite remarkable, actually; there are about 30. You can look at every series in mass media and say, “oh yeah, that image looks like thousands of others.”

This is not a very original thought, but perhaps this is the reason we have become so inured to these types of images. Basically, they are carbon copies of one another. As you know very well, once you see enough of something, you stop seeing it. You start to become immune to their emotional effects.

I became a fellow at the Library of Congress about two years ago. My research project was to look at old documentary and propaganda films. I started with collections from Vietnam, and from Germany, Italy, and Japan from World War II. I also looked at still images from World War I and back to the Fenton images. I tried to identify visual tropes, and then I rephotographed them, to use as source material for my image-making.

I found that regardless of the maker, whether it was a German or an American or a Vietnamese, I saw the same kind of image construction. Sometimes in the 1930s, for example, you would see the same newsreel footage used on different sides of an ideological conflict. We’ve somehow continued to create mystification of conflict through the use of images. When we look over the expanse of history, we find that we haven’t got very far.

GREGORY: WITNESS is a human rights network. We were founded after a very iconic incident in 1991, when an ordinary person shot video of Los Angeles police violently striking a man, Rodney King, after a traffic stop.

In some ways, our vision was ahead of its time. For the past 25 years, we’ve grappled with a kind of contradiction. Seeing is not necessarily believing. No piece of video, whether shot by a citizen or a journalist or a police officer, is trustworthy in and of itself. We want to contest these videos. On the other hand, we also want to reflect on their intense potential value, particularly since the digital revolution can reflect a vast array of human rights realities that weren’t seen before.

Over the past 25 years, WITNESS has worked with progressively larger concentric circles of people who have access to image-making technology. It was unusual that George Holiday was able to film the Rodney King beating. It was dramatic. George Holiday had lived under the Argentine dictatorships and was someone who had a sensitivity to human rights issues, but he hadn’t bought the camera to film human rights violations. He just looked out his window and saw what was happening. For many years, we worked primarily with nonprofits and NGOs around the world on a range of issues, from land rights to elder rights to war crimes.

Over the past 15 years, we’ve seen an explosion of grassroots mobile video documentation and a related growth of people sharing false accounts. We’ve been a part of the growth of a movement of video as evidence, which is also reflected in the work of groups like Bellingcat. You can both proactively help individuals document their reality, and you can analyze the reality shot by perpetrators or by ordinary civilians and turn it into evidence.

One thought that strikes me as I listened to you, Ivan, is that so much of that is training people to fit into preconceived patterns. The nature of video as evidence plays into the idea of teaching people to fit the expectations of a judicial system, which is very different from the expectations of what you might show to your community or to mobilize public opinion.

How much should people try to fit within the boxes of institutional power, and how much should they try to challenge those constraints? What is the balance within that? In the last 18 months, I’ve been focused on deepfakes — a new generation of ways in which you can manipulate video and audio to make it look like someone did something or said something that they never did.

The nature of video as evidence plays into the idea of training people to fit the expectations of a judicial system, which is very different from the expectations of what you might show to your community or to mobilize public opinion.

That has been possible for 20 years. Both Ivan and I like to place things in a historical context. Nothing is ever new. But what is new about deepfakes is the accessibility, the ability to do it more seamlessly, the ability to place it into an environment of distrust that makes people more likely to want to believe it. I’ve spent the past 18 months looking at this question, in this recursive loop of people saying something is fake. No, it’s not a fake. Prove it’s not a fake. I can’t prove it’s not a fake. Therefore, it’s a fake.

How do we defend the fact that there is still real value in this explosion of citizen documentation while reconciling ourselves to the challenges we’re facing? A lot of distrust at the moment, including what people are pushing on social media platforms, is driven by a sense that nothing is going right.

We’re all pretty privileged, sitting here listening to a gallery talk in the U.S. When I look globally, I see plenty of places where there was never any mainstream media, where there was never any kind of institutionalized truth-checking apparatus. How do we defend the fact that some of the incredibly flawed infrastructure of sharing information, like Facebook, has also facilitated tremendous benefits in some ways? I think that’s important to name when we’re in the U.S. because so much of the decisions are driven about 150 miles from here in DC or 3,000 miles from here in Silicon Valley and have very little to do with the rest of the world. I think as we have this conversation, we also need to consider who is missing in this discussion. What do they want out of these sorts of image-making apparatus and distribution systems?

SIGAL: In the last 25 years, we’ve moved decisively away from the conventional idea of photographic images as representation to acknowledge that images are evidence. Today the camera itself is recording all of the metadata. The kind of contextualization that we used to do around images is now intrinsic to images themselves.

With the mass spread of CCTV, we have gained knowledge and awareness of how we change our behavior when we know that we’re being observed in social spaces at a mass context. The ubiquity of image-recording devices is also changing the way we are in the world.

Those of us who have grown up in an image culture have traditional narrative techniques that we use for making images. But we now experience cameras as an element in how we organize society. Some of what was latent in the analog era of image-making is now explicit.

GREGORY: With the activists we work with, you see a lot of very nuanced understanding about decisions to share images because of the implications for safety. Decisions around live streaming: How do you make that decision in a way that is informed by distribution? I’m not going to use the word “democratize” because that’s a terrible phrase for this, but you see a much greater sort of media literacy on the nuances of using images.

I think about image-making around police violence. We’ve actively trained groups of people making decisions about holding back images. When is the right moment to release a video of police violence? You want to use it as a counterpoint to the police account, not as the precursor. You don’t have first-mover advantage. If you release it first, you get explained away. You allow the police to say, “No, you didn’t see what happened before…” If the police account comes out first, then you can reveal the failings in that account.

SIGAL: There’s also the question of the chain of custody of imagery here. In the backroom of this gallery is a compilation of two pieces of newsreel footage made by a German newsreel company in 1934. The images come from a moment in which the New York National Guard faked a Communist demonstration, suppressed the demonstrators with tear gas for the German newsreel company to film, and then broadcast back in Germany. This is, apparently, the American military collaborating with the Germans to make anti-Communist newsreel propaganda in August of 1934. A voiceover comes from a May 1934 gathering of 25,000 ethnic Germans in Madison Square Garden to protest the US embargo of German goods.

We have these pieces of evidence that the US is sympathetic to the German cause in different ways in 1934 after Hitler has taken power. Both of these pieces in the German newsreel footage don’t give you quite enough information to say for certain that this happened in the way that the newsreel claimed that it happened. There is a break in what we call in forensic language and evidentiary language, the chain of custody. The Germans claimed that the film was made in collaboration with US military. It’s probably true but difficult to absolutely prove it. That’s just an example of noting how this issue is always present in the creation and construction of images.

Today, in the context of digital production, when you can’t trust the image as an artifact in itself, demonstrating the chain of custody from its creation to its distribution to its release has become an increasingly elaborate exercise. If it’s been changed or manipulated in any way, you want to have a complete record of those changes.

GREGORY: I’m curious to hear you talk more about archives because I’ve worked in this space for about 25 years, and we honestly didn’t talk much about archives in a meaningful way 25 years ago. We thought about them as libraries, as places that preserved our footage. Witness has an incredible archive of older human rights footage, but I don’t think most human rights activists thought much about archives. There wasn’t much volume. It wasn’t like you had a terrible problem trying to track your footage. You had a set of tapes on your wall, and you could pull out the one you remembered. It’s a sea change. In the last few years, we get more requests for trainings on archiving — managing your media, tracking authenticity, tracking what you have — than anything else. That’s a really interesting sort of shift.

When you can’t trust the image as an artifact in itself, demonstrating the chain of custody from its creation to its distribution to its release has become an increasingly elaborate exercise.

At the same time, we see something interesting happening now. When we’ve done threat modeling around deepfakes, people point to these archives as the perfect thing to mess with because there’s plentiful footage of public figures who don’t have a right to challenge it. There’s all this content that can be faked and forged and changed unless you’ve tracked it well. I’m curious how you think about archives in the digital space.

SIGAL: I’m really interested in the moment of transition from analog to digital archives because the natural state of an analog archive is slow disintegration. A lot of times, archivists will not be cataloging point-by-point at the level of the object. They will be cataloging at the level of category. With the film archives that I worked in, a lot of the material has not been seen. It was collected and very loosely cataloged. There’s no description — or a very bad description — of what’s collected. You have to watch it to know what’s there. If there’s a master copy, they may not let you watch it because it’s a negative and if it gets destroyed, there’s no positive. Part of my work with this project was to see how much they would let me repurpose in digital space. And that was kind of a provocation. If something had a copyright on it, would they let me bring a camera near it and refilm it or not? Did I have to obscure it in some way?

An archive is a set of rules with an underlying narrative. What fits within a collection, and what is excluded from it? It’s much, much easier to spin up an archive in a digital space. But those are also probably not intended for posterity in the same way as a traditional archive. If you have to go to the trouble of building a physical archive, you need significant resources to maintain it and you’re expecting it to be around for a long time. A digital archive has a different temporality.

The Library of Congress, starting around 2010, built a set of online collections around events. For example, they made a collection of material from the end of the Sri Lankan civil war. They scraped everything they could find on that topic. And then they encapsulated it and built a bunch of metadata around it. And now it just kind of sits there.

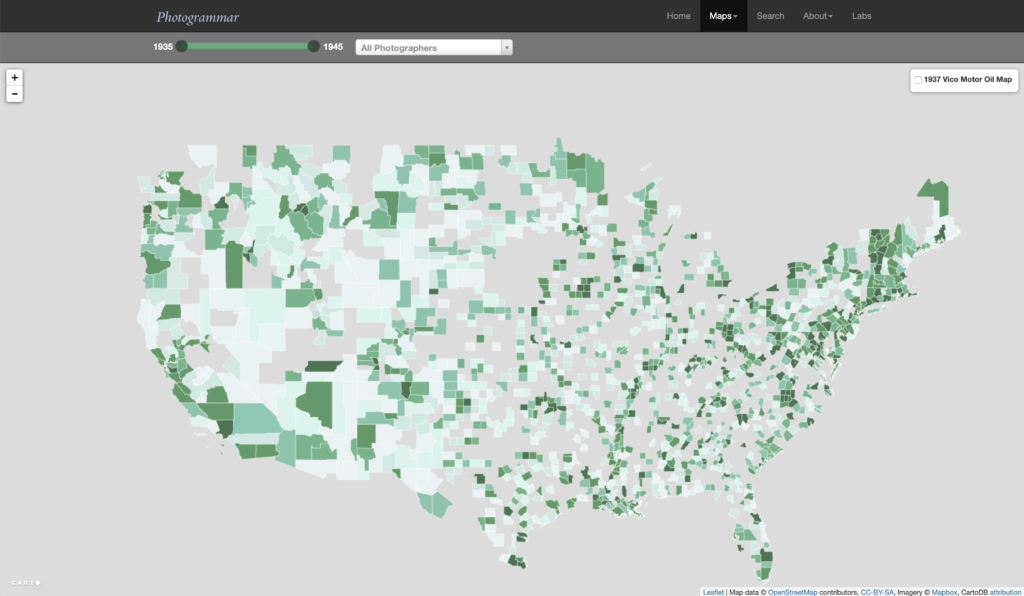

Another example from Yale and the National Endowment of the Humanities is Photogrammar. It’s a web platform for organizing photos from the 1930s United States Farm Security Administration and Office of War Information (FSA-OWI). It’s got very extensive and very granular metadata architecture, and most of the images are digitized and available online. Whether something is originally digital or not, with an archive space, what becomes important is the narrative you set for it and its limits — what you exclude from it. Otherwise, it could just be absolutely everything.

GREGORY: We worked on a project with trans and gender-nonconforming people, around violence against those groups in the US. That was a curation project to show the level of violence trans people face, particularly trans people of color, trans women of color. This was a couple of years ago, and the national conversation was focused on trans people’s rights to access bathrooms. Clearly, it’s a part of a conversation about rights issues, but it was being used to minimize this discussion and almost made it seem petty. These groups were asking: How do we show the level of violence happening, given that the federal government is not gathering the needed statistics?

We looked for videos shared online that show assaults on trans people or gender-nonconforming people, videos that are celebrated. I’m hoping most of you have not spent much time looking for transphobic hate videos. There are a lot of them. Those shot to celebrate assaults vastly outnumber the number of witnesses who film these attacks in a sort of evidentiary way.

And this is probably true in a number of other scenarios. There’s a distressing number of videos of war crimes shot by the perpetrators. This is not unusual. It tells you that there is a sort of hidden archive that can provide this data point. None of these videos were shot with this purpose. None of them were filmed as evidence. They were filmed to celebrate violence. But when you do this scraping, you see a massive number of these videos and a massive number of likes and approving comments. So, you have sort of parallel data sets of people choosing to celebrate this. Hundreds of millions. These individual videos are not something we would want to share. In this project, we didn’t share the videos that we were using as data. We were flipping the intention of the filmmaker, the intention to celebrate and to have it watched. We are not gonna celebrate it. We’re not gonna let people watch it.

Transphobic hate videos are shot to celebrate assaults and vastly outnumber the number of witnesses who film these attacks in a sort of evidentiary way.

SIGAL: One of our challenges is around the areas of absence or of ignorance. When we look from a perspective of historiography, we talk about the things we know about. We don’t talk about the things we don’t know about. A big part of our work is searching out under-representation or looking for a lack of documentation. We’re trying to figure out where else we should be looking. What you’re talking about is almost the opposite. It’s a strategic silence, flagging, and identifying material that you think of as a kind of terrorism. I’m not a big fan of many efforts to “counter violent extremism,” but with the hateful and often illegal expression the makes up online violent extremism there is an effort to identify this material as a sort of archive and then obscure it from public view. Is that correct?

GREGORY: Yes. YouTube, which is where many of these videos were found, does an overly “good job” of removing extremism content and war crimes footage.

SIGAL: Which means you can’t use these works as evidence because you can’t find them.

GREGORY: But they hadn’t done a very good job of removing this violence. How they define unacceptable violence is very much determined by where the political pressure is. These videos up on YouTube have tons of views. They’re not invisible. Some have millions, while war crimes video that might be perceived as terrorist gets zapped by the algorithm pretty quickly. There is a political statement around algorithms and power. YouTube is allowing the visibility at the same time as we’re trying to say, “We don’t want to make this visible. We want to use it as data.”

SIGAL: The dominant political narratives about what is perceived as a threat — in this case, terrorism — is the thing that gets the attention, the money, the algorithmic suppression. Ideas that are not perceived to be a threat are allowed to flourish. In the last 15 years, it’s clear where all of that energy has gone and where it has not.

AUDIENCE QUESTION: You mentioned that YouTube does a good job of censoring certain videos and taking them offline, but not when it comes to violence against trans and other nonconforming communities. Is that what you were talking about before about norms around how we define violence? In this case, they’ve defined violence as terrorist violence and ignored violence against oppressed communities?

SIGAL: Yes, that’s correct. The violence they’re looking for and what they’re willing to spend energy and resources on suppressing correlates to the political pressure that they’re getting. They’re not taking down hate speech or targeted threats against women in Pakistan, for example, of which there’s also a huge amount. But they are taking down terror threats linked to state power.

GREGORY: Yeah, and even with violent extremism, they’re probably taking down less right-wing Hindu nationalist content and less American far-right content and more extremist Islamic content.

The other changing dynamic over the past three or four years is the increasing use of AI algorithms. The training data that informs the algorithms has bias in it that sets it up to flag some things and not others. They’re not setting it on transphobic violence, but as they put it on something like extremist content, what are they picking up? It’s the data points they fed in.

SIGAL: Sam, can you explain briefly how human interpretation comes into an analysis of those datasets for YouTube?

GREGORY: With content moderation on YouTube, the vast majority of extremist content is removed automatically. It comes out of an algorithm that has training data from previous examples, mostly of perceived violent Islamic extremism. There is almost no transparency on the datasets. In the last couple of years, there’s been a significant struggle in the human rights community involving many groups, including one called the Syrian Archive based out of Europe. One summer day in August 2017, hundreds of thousands of videos of Syrian war crimes disappeared from the internet. They disappeared from YouTube because YouTube had altered its algorithm. And the algorithm now saw all these videos that had been shared as evidence of war crimes — they’re often violent but are clearly labeled. This is evidence of a bombing or clips that demonstrate war crime. They just blipped off the internet overnight. It’s a reminder of the power in these algorithms and the choices made about the data. It wasn’t a human choice at the point of each item. It was a choice made at the start of building and maintaining the dataset that fed into that algorithm.

SIGAL: This goes back to the beginning of the conversation because for a computer algorithm to be able to see certain types of images, those images have to be representative of a type. In other words, a trope. We see these types of images in a certain way, and we conduct ourselves in accordance with the expectations of those images. Think about terror acts in the 20th century versus the 21st century. Terror acts in the 20th century were created for mass audiences. They were epic in scale. They’re sensational in form. They’re meant to frighten. They’re meant to be rebroadcast in mass media. The apex of that is 9/11.

In contrast, 21st-century terror acts are created for your individualized screen, just like every other kind of media event. The essential 21st-century terror act is the beheading of a single journalist in Syria by ISIS. One person, one death witnessed by you, alone. It’s a major shift in terms of how terror is conducted and how we witness it. But both of those kinds of acts still maintain the expectations of the narrative of how we’re gonna see them. And then Hollywood will pick them up and reprogram them for its own storytelling purposes, which then retrains the next generation of people who are fighting in wars to imagine themselves in playing that same role.

I remember the first time I photographed war. The Chechen paramilitaries all dressed like Rambo. They took their cues for masculinity from Hollywood. They understood how to act as soldiers from watching films, except they all wore these little high heel boots. So there’s this kind of curious circularity that’s between representation and action in the world that then feeds back into the next generation of representation.

Terror acts in the 20th century were created for mass media audiences and were epic in scale. In contrast, 21st-century terror acts are created for your individualized screen, just like every other kind of media event.

AUDIENCE COMMENT: The summer events in Hong Kong remind me of these dynamics. I’m thinking of the toppling of the surveillance pole. People were wearing face masks and making other efforts to protect themselves from the surveillance society.

SIGAL: At Global Voices, we have an amazing writer and editor from Hong Kong, Oiwan Lam. She runs her own human rights media activism project there, inmediahk.net. Oiwan has probably written 30 stories in the last six months on this topic, so everything I know about it comes from her.

The extent to which protestors in Hong Kong have chosen fluid tactics around their work is remarkable. They’re so aware of this surveillance function, and they have a model of being like water, constantly changing their tactics and trying to confront or confuse the surveillance approach — everything from the routes they’ve chosen to walk to ideas around simultaneous pop-up demonstrations around the city. Rather than having a parade, they are appearing en masse on the streets and then vanishing into normal every day, pedestrian traffic. All of that is a way of attempting to frustrate the traditional mechanisms of public control. And it’s a contest because as soon as they try one technique, the authorities come up with a way of suppressing it, and then they have to try something else. For example, the state responded by sending groups of thugs out in the suburbs and beating people in subways to send a message: Don’t try a pop up demonstration here, folks. We know you’re doing it.

GREGORY: Witness doesn’t work closely in Hong Kong, so I don’t have those insights. But we’ve seen a constant tension with activists using video over the past decade, a tension between visibility and anonymity that gets ever more acute. How do you manage expectations that you should either stick with one or the other? The reality is that one day, you desperately want people to be paying attention to you and another day you want to be anonymous. The way we are tracked on mobile devices does not facilitate that choice, nor does it enable what we were talking about earlier: the movement towards demanding that people working in journalism share more metadata, share more proof that it’s them creating content. That’s a double-edged sword. Sharing more data to prove who you are is sharing more data that can be used to track you down.

The other thing we see globally is push-back on the right to record. Governments have recognized that there is something powerful in citizens filming and are attacking that right, legally and extra-legally. It is a globalized trend. It’s happening less in the US because of jurisprudence, but it happens extra-legally all the time; for example, people who try to film the police face trumped-up charges or assault.

We don’t know where this goes in terms of protecting anonymity in a crowded environment where you have multiple surveillance sources. I would not be optimistic about people’s ability to evade that.

SIGAL: People in Hong Kong know that they’re being watched and are left hoping that there are so many of them that the state won’t be able to suppress them all. Which is the only tactic you have left at a certain point. I’ve seen that in other places. I was in Russia in 2012 during a wave of protests. Activists assumed that they could not maintain anonymity, that they wouldn’t be able to attain organizational integrity, and that there would always be people within their networks who would betray their trust. There are spies. There are moles. Russians are also very good at physical surveillance.

Sharing more data to prove who you are is a double-edged sword—it’s sharing more data that can be used to track you down.

If you think you can beat that kind of focused state surveillance, you’re wrong. But the Russians have always been especially good at it. As an organizational tactic, everybody who ran those events basically said, if you want to be part of the movement, you have to agree to let your life be entirely transparent. You won’t have privacy.

As a fascinating counterpoint, the other challenge those activists face is getting attention. We would ask many of the folks that we worked with in the Arab uprisings: Are you aware of your physical security or digital security? Are you paying attention to these issues? And they said: “Our biggest problem is being visible. We care much more about that than whether or not we’re secure.” Once again, we have these two clusters of contradictory questions.

GREGORY: Let me add one note about transparency. A lot of the discussion around deepfakes is centered around the usual suspects: Is Senator Rubio going to be hit by a deepfake? Or Donald Trump? Maybe, but they’re pretty well-protected should that happen. The people who are vulnerable are the ones who already face targeted sexual-image attacks, reputation attacks — particularly female journalists and activists. In movement work, you rely on your credibility and your reputation, and you also are extremely vulnerable to those types of attacks because you don’t have security around you. You’re not an institutional figure.

SIGAL: Traditionally, from a human rights perspective, we distinguish between ordinary people and public figures when it comes to defamation and libel. Politicians and other public figures don’t get a pass. You even make it harder for them. But authoritarian regimes tend to create special classes of law for their leaders. They tend to say it’s criminal to libel the president, for example.

We’ve had this curious moment in this country where it appears as if the social media companies are creating a special set of rules for politicians and other public figures when it comes to what is acceptable on their platforms. Trump regularly gets a pass in terms of Twitter’s terms of service. Others would not get the same pass. And that is similar to replicating what Kazakhstan would do for their president in terms of saying, well, Nazarbayev gets a pass: if you libel him, we’ll put you in jail. But if you libel the guy around the corner, no problem. There’s this creeping trend within the choices that companies are making, which they’re making for entirely self-interested reasons, around popularity and attention

AUDIENCE QUESTION: I don’t disagree, but can you articulate, how do you think it does that? How they get a pass?

SIGAL: If you violate Twitter’s terms of service and they are aware of it, they will censor you. They will give you a timeout. After about three strikes — I don’t remember the specifics — they’ll kick you off. They have rules about what you can say, and how you can act if people complain about you. Things like hate speech, incitement to violence, targeted expression against groups aren’t allowed. Every company has its own terms around what is and is not acceptable speech, but, in general, those are the parameters.

GREGORY: I think President Trump on Twitter has been in violation in a number of cases. A human rights activist who did the same thing would be thrown off in a heartbeat.

Another question is whether political ads be fact-checked. Should a fake ad? How do you define a politician? I look at these things through a global lens, but a lot of these rules are responding to a US context. How do they play out if you put them in the Philippines or Brazil, where you have even fewer rail guards and much more political pressure on the platforms? In Hun Sen’s Cambodia, there is clear pressure directly from the government on Facebook in terms of decisions they make on the platform.

AUDIENCE QUESTION: What kind of organizing is happening in terms of people contesting those kinds of rules?

SIGAL: There’s a huge amount of contestation around those rules. Almost every day, you’ll see an editorial about it. In the U.S., there’s a kind of moral panic that I think is somewhat deterministic. For example, Facebook may not be right to avoid responsibility for whether or not political speech is factual, but, actually, that is not Facebook’s issue. That’s a legal precedent that’s been around for quite a while. I can tell you for sure that the media outlets that are complaining about Facebook not doing it are also not doing it. ABC, CBS, CNN, FOX News, they can also broadcast political advertising that is not true, and, in fact, they are obliged to do so if they choose to broadcast political advertising.

GREGORY: I think one of the good things to come out of this has been more and more pressure on the platforms to do it better. The most visible thing here in the U.S. is this sort of moral panic and commentary, but there are increasing numbers organizing in the Global South. Groups like the Next Billion Coalition, which comes from Myanmar and India and elsewhere, are asking to be directly in dialogue with companies. And there is also much more activity among minority communities. People of color in the U.S. have said, “You need to be listening to us.” The Leadership Conference on Civil Rights and others have also said that to Facebook.

Now, is that balanced against incumbent power within those platforms? Facebook has pulled in a lot of conservative policy figures to compensate for the new administration, who are probably setting much of the policy within Facebook at that level. So, there is seesaw-ing going on here.

I think what really matters is how the U.S. debates transfer globally. What’s most important is that we hear the voices of people equally, particularly those actually being harmed in the U.S., not merely those who perceive a harm, and that globally we are listening. Otherwise, we’ll come up with yet more poor solutions. We only need to look at Myanmar in 2014 to 2016, where Facebook is arguably culpable in a genocide — or, at least, accessory to genocide — to see what happens when this is not done well.

SIGAL: Or Duterte’s election in the Philippines in 2016. There are many examples. There are other interesting attempts to try to get companies to follow international human rights norms and standards because there is a large body of precedent and international human rights law around how to handle these issues. But the companies are resistant to doing that. They will certainly listen to the people who are speaking from that context. For example, the UN has a freedom of expression rapporteur who’s very sharp on these issues, David Kaye.

But policy people at most companies will not accept these restrictions in practice, even though it could solve a lot of problems for them. They could say, “Instead of the random mishmash of rules that we’ve created for ourselves, we can use this established international norm.” But their challenge then becomes liability. Once they accept that kind of external standard, they would have to stay with it. And so they’re really trying to avoid accepting some kind of norm. They are future-proofing against some change in their business model.

GREGORY: You may have heard of the Facebook oversight board. It adjudicates these content-moderation decisions, the really tough ones. They just launched it to use international human rights standards in the board’s decisions. But I think it may be of the same piece as you’re describing. They are saying: “This other group can make decisions with this, but we’ll take those decisions at an individual level around case X or case Y.” In some sense, they are offshoring the human rights to this other body. But it’s an interesting moment because it illustrates that people have fought to bring more attention to standards that have been agreed by over 170 countries. We’ll see where that goes.

AUDIENCE QUESTION: A group of civil rights leaders is meeting with Facebook next week. What should they ask?

GREGORY: I think there’s a set of things that they should be demanding. One of the problems at the moment is a false parity of concerns around everything from fake news to hate speech on Facebook. The most extreme harms on hate speech, both in the US and globally, affect people who are marginalized and vulnerable in societies — typically minorities of various kinds. We have to push back on the false parity and say, look, this isn’t just a PR decision. This has real human implications for communities.

And, then, it depends on the products. In general, there’s a set of questions: How transparent are you about how you handle this content? How do you handle hate speech? If someone is accused of hate speech, how do they challenge that? At what point is speech taken down or not? Transparency is a huge part, as is acting in ways that support international human rights law or US domestic law. There is a vast range of responsiveness, which goes back to what we were mentioning earlier about terms of service. In this case, they’re not paying attention to hate speech, to aggression towards people who are already facing threats. So it’s the false parity, it’s transparency, it’s genuinely investing resources in implementing policies and making sure those policies have a genuine rootedness in accepted standards.

SIGAL: We often find that the companies will dismiss criticism by saying, “You don’t understand what’s happening. You don’t see the data.” It’s a trap because, of course, we don’t know because they won’t give us the data! We’re operating on assumptions. If you make a wrong call, they are able to dismiss you outright. Figuring out how to break that paradigm is something they need to hear every single time we talk to them.

What might be a good policy for the UK could have extremely adverse effects elsewhere in the world. It’s really hard to use international bodies to say, “China, you’re doing the wrong thing” if the UK is doing the same thing.

GREGORY: I think we’re seeing more cross-Global South solidarity and pushing on Facebook. I would love to see solidarity that’s also cutting across, from the US to communities in the Global South around making sure that we don’t argue for things that are counter-productive for people elsewhere. People argue for solutions that might work well if implemented at scale and with all of the resources that Facebook will put to bear here. But those remedies might have very unexpected consequences elsewhere, where they’re not resourcing it, where they don’t care whether governments will abuse it.

SIGAL: This is especially true around regulation. The British government right now is attempting to regulate social media companies based on what they’re calling “duty of care,” which in the US is about tort law, it’s about public health harms. A duty of care argument is problematic in the speech context for sure. But beyond that, it also requires a competent judicial system and the ability to follow through any punitive measure.

If the British implement that kind of rule, you will see copycats in authoritarian contexts that will be not based on a similar set of democratically approved decision-making processes. They will be used to target specific groups. What might be a good policy for the UK, could have extremely adverse effects elsewhere in the world. And those policies could justify those other policies. It’s really hard to use international bodies to say “China, you’re doing the wrong thing” if the UK is doing the same thing.

Freedom of expression in a digital context is that the fact of expression can also silence an opposition. Expression has to be understood in the context of people also available to listen.

AUDIENCE QUESTION: Ivan, you’ve often reminded me of how this is not new necessarily. There’s a long history. But can you both talk more about that, as we enter the election cycle in the years ahead? Will misinformation and disinformation be further weaponized? What are you reading?

GREGORY: The lens I viewed this through in the last 18 months is where deepfakes land. People come to me and say, “We’ve had this before. We’ve had Photoshop, and we survived.” And my response to that is Photoshop didn’t land in the same type of information environment as deepfakes do.

Whenever we assess technology innovation, we have to look in the societal context of what we’re ready to do, as well as a whole bunch of other constraints around it. For example, we are less well-prepared cognitively to handle deepfakes video and audio, as we are with photos. But I think the critical element is the broad-scale weaponization of images and video, which is now available to people from state actors down to designers in boutique shops.

The flip side of that is we also have historical experience. With a lot of the work we’ve been doing in the deepfake space, we don’t view this as a complete rupture. We see this as an evolution. We’ve worked out how to disprove content online. We have people thinking about verification and fact-checking. These provide partial solutions. But if we reduce it to just one element like deepfakes or bots, we’re gonna fail. We need a much broader context of how we reinvent the ways we think about trust. We need to shore up things we care about for some populations — and also target what we do. A significant percentage of people in most societies still care about factual information. I’m trying to think of it in those terms. How we deal with the weaponization right now is pretty critical.

We spent a lot of the last 12 months talking to people about solutions they want, and there’s kind of a solutionism starting to happen in deepfakes work led out of DC, Brussels, and Silicon Valley. In some ways, that’s good. People are trying to get ahead of the problem before it’s too widespread. On the other hand, it’s precisely the problem we’ve had before. We’re gonna solve it with a technical silver bullet. We’re gonna come up with startup ideas and forget about the people in Myanmar, the people in Brazil, the people who live in the middle of the U.S. All of those questions are gonna happen again.

SIGAL: All of these ideas and forms have been around for a very long time. But, historically, there are moments in which more is different. I was recently talking to someone who works on forensic data analysis in the Philippines. Their adversaries are setting up websites all around the world and linking them. They’ve using different troll content farms and troll groups; they’re mobilizing computer networks to overwhelm people with a volume of expression that is physically unmanageable and hateful at the same time.

At a certain point, what we understand about freedom of expression in a digital context is that the fact of expression can also silence an opposition. Expression, which is a cherished and primary value in the United States, has to be understood in the context of people also available to listen. When we build our technological platforms, we often talk about the responsibility to listen, paired with the right to speak. In a very simple way, this means that we organize our information architectures so that whenever we’re saying something, we make sure it can be heard. There are all sorts of questions around morality and power and authority within that framing. It is possible to build conversational spaces that support people who come from different positions, with different language skills, and different education levels.

We are often suggesting solutions without understanding the problem. We still don’t know to what effect the Cambridge Analytica misinformation scandal had on the 2016 elections. We simply don’t know.

Most of our commercial social platforms do not do that. They privilege expression to the detriment of listening. And they do that at a pathological scale, which is why we have the kinds of social media that we have at this point. There are some solutions for them. Still, the misinformation piece is an addendum to much larger pathologies around how we construct our spaces for expression because they are built to be available for that kind of abuse.

That said, we still don’t know what the actual effects of that kind of expression are. We focus our research on trying to understand what expression is and who’s making it. A lot of times, it’s toxic, but in many countries, it is perfectly legal. There’s no easy way to deal with it from a regulatory perspective. Even when we can see it, our ability to make an actual accurate claim about it is still basic. For example, we still don’t know to what effect the Cambridge Analytica misinformation scandal had on the 2016 elections. We simply don’t know. That’s the best we can say about it.

I read a report produced by Rand about five or six months ago, called Countering Russian Social Media Influence. Rand published a study that begins by saying, essentially: “We don’t know anything.” And then it goes on for roughly 60 pages of solutions, which is insane because they don’t actually know what happened, and yet they are suggesting a bunch of things to fix a problem that they can’t even articulate.

As it happens, I read the report and think that most of their suggestions are wrong or harmful. Our state of knowledge in this is really quite low. We don’t know what’s happening. We don’t have the social science techniques to be able to study this. We have a field of expertise, public-opinion polling, and surveying, which is often broken these days because people don’t answer their phones anymore. And then, we have analysis of big data sets as a separate field of expertise. Different people have different educations, they don’t talk to each other, and you can’t easily collate those approaches, which gives us a big hole in the kinds of knowledge we have. And that leads us to a place where we are often suggesting solutions without knowing what the problem is.

To Sam’s point, we will know eventually. We will start to regulate regardless. The Europeans are already regulating, and we will see their effects. Some of those effects will be positive, and some will be negative. But we’re operating in a realm of uncertainty and lack of knowledge in the space.

GREGORY: If you want recommendations on people to read, I’m gonna throw out four names you can follow on Twitter. You don’t have to read books by them. Claire Wardle (@cward1e) at First Draft, who really follows misinformation, tactics. Renee Duresta (@noUpside) and Camille Francoise (@CMFrancoise) who are deeply involved in the analysis of disinformation and Maria Ressa (@mariaressa) in the Philippines; she co-founded Rappler and has been at the front of using social media for news distribution.

SIGAL: And I’ll give you a few as well. Follow David Kaye @davidakaye, the UN rapporteur for freedom of expression. He recently wrote a short volume, Speech Police. It’s light. You can read it in an afternoon.

I’m biased, but there’s a project called Ranking Digital Rights, run by Rebecca MacKinnon, one of our colleagues, that does a very admirable job of explaining how different companies create different policies for freedom of expression, and then ranks them based on human rights norms. It’s a very good place to try and get your mind around what those things are.

Finally, Yochai Benkler’s Network Propaganda is the best book I’ve read on misinformation in the 2016 elections. He concludes that most of the narratives that we think of as coming from social media, actually come from or are amplified by mass media. And that the claims that we’re making about this being only a social media problem are actually not correct.