This past week I’ve been in Colombo, Sri Lanka. It’s been about a decade since I was last here, and in the interim the country has concluded a nasty war against the LTTE — the Tamil independence movement — and a new, fragile reconciliation government has come into power. Naturally I’ve been thinking about the war, its aftermath, and inevitably how it was depicted. But the images that come to mind are neither the genre war photos of soldiers discharging guns, nor the social landscape imagery of silent battlefields, such as the Fenton image of the Crimean War.

Instead I primarily recall satellite images of the last remaining territory controlled by the LTTE, on the Northeast coast. Provided by the UN agency UNOSAT, for sale from commercial satellite operators and also visible in Google Earth at lower resolution, these images show houses, schools, hospitals, roads, first intact and then destroyed.

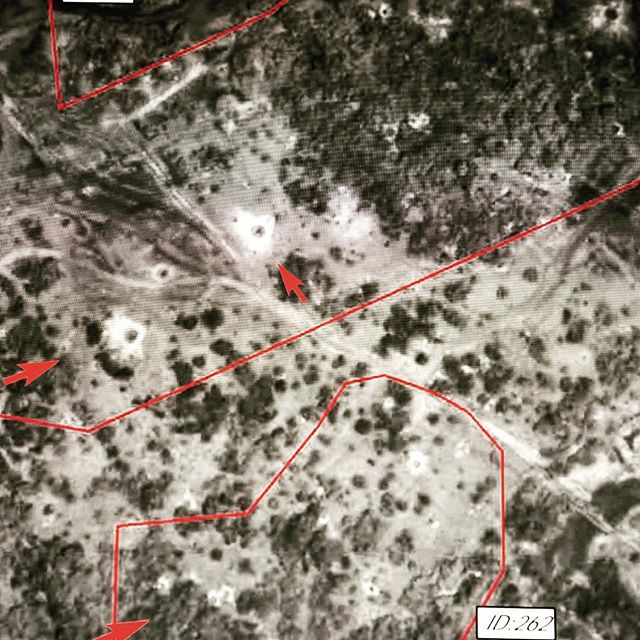

As the war drew toward its conclusion in May 2009, a civilian population living in Mulattivu District collected in a protected “Civilian Safety Zone.” A comparison of satellite images subsequently showed intense bombing of that area, with visible craters, damaged buildings and over 1,300 grave sites. These photos are evidence of the location of fallen shells, targeted buildings, shifted populations. There are extensive, detailed, published analyses of these images, pointing to possible war crimes.

We typically claim to find forensic meaning in these images, and consider their descriptive power to be primarily evidentiary. And yet, just as with photos of bodies holding guns and moving through space, I find myself drawn to the aesthetic and narrative qualities of these degraded and often blurry depictions of the earth’s surface, gridded over with lines of longitude and latitude, elaborated with arrows, demarcations and notations. These fields, forests, plains and mountains that once were battlefields.